Post-Stroke Recovery: Can Stimulation Of The Vagus Nerve Help?

(Posted on Friday, February 16, 2024)

This article was originally published on Forbes on 2/16/2024.

This story is part of a series on the current progression in Regenerative Medicine. This piece discusses advances in vagus nerve stimulation.

In 1999, I defined regenerative medicine as the collection of interventions that restore normal function to tissues and organs damaged by disease, injured by trauma, or worn by time. I include a full spectrum of chemical, gene, and protein-based medicines, cell-based therapies, and biomechanical interventions that achieve that goal.

One of the key issues for stroke patients is the recovery phase. In addition to rigorous physical rehabilitation, a new twist may unlock stronger recovery from stroke patients: stimulation of the vagus nerve. In a recent unveiling at the International Stroke Conference, Dr. Teresa Kimberley and colleagues describe an approach to post-stroke regenerative medicine that pairs vagus nerve stimulation with upper extremity rehab. They present the results of a trial in which 53 participants received treatment and dramatically regained upper arm mobility. Here, I will analyze their treatment and the described trial and discuss them in the context of the future of regenerative medicine.

The vagus nerve is among the most important subsections of the human nervous system. It is involved in parasympathetic processes of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. Additionally, the nerve plays a noted role in healthy brain function.

Vagus nerve stimulation is the therapeutic application of low-amperage electrical signals to the vagus nerve. While the stimulation is localized, its effects are felt throughout the body, affecting the bodily functions in which the nerve is involved. Some uses include the treatment of depression and other mental health ailments and improving heart rate stability.

Kimberley and colleagues use vagus nerve stimulation in a slightly different context. During a stroke, blood flow to a certain portion of the brain is limited, resulting in the damaging or killing of affected cells. Limb mobility may be limited post-stroke if those cells lie in or around the motor cortex.

However, Kimberley and colleagues found that sustained vagus nerve stimulation paired with upper limb mobility rehabilitation resulted in profound improvements in patient mobility in a short time frame.

Their first study, released in 2018, involved a cohort of eight patients fitted with a vagus nerve stimulation device that delivered 0.8 mA consistently for 90 days. They, alongside a control group, received upper arm rehabilitation treatment for six weeks, three times per week. Results were measured one, seven, 30, and 90 days post-treatment.

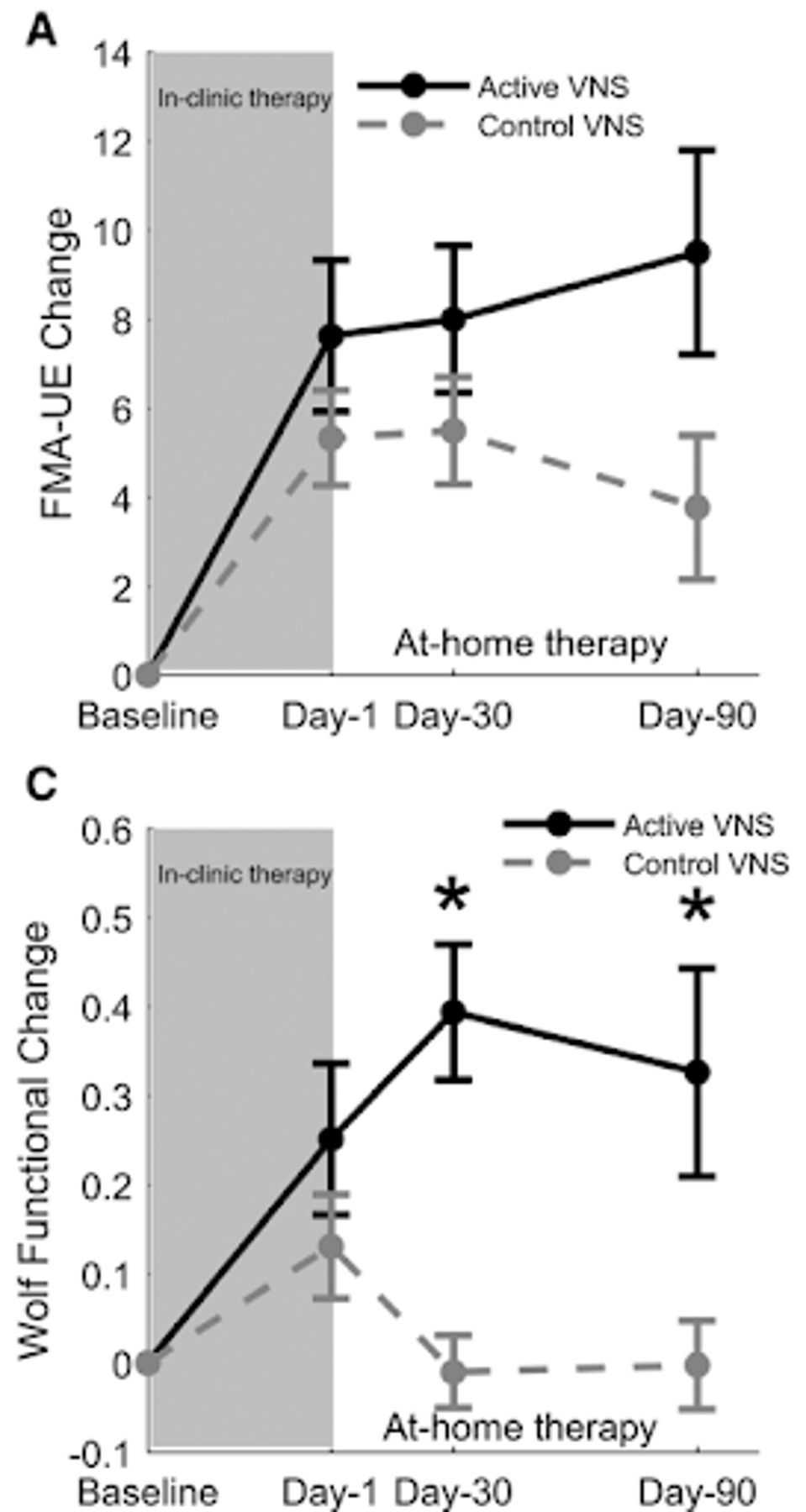

The researchers used the Fugl-Meyer Assessment and the Wolf Motor Function Test to determine motor recovery and function in stroke patients. They assess physical impairments, focusing on motor function, balance, sensation, coordination, and joint functioning through various tasks and activities that result in a standardized score.

In both tests, patients who received stimulation and therapy improved their scores dramatically compared to those who just received physical therapy.

FIGURE 1: Changes in upper arm mobility over time in patients who received vagus nerve stimulation and therapy vs those who only received therapy.

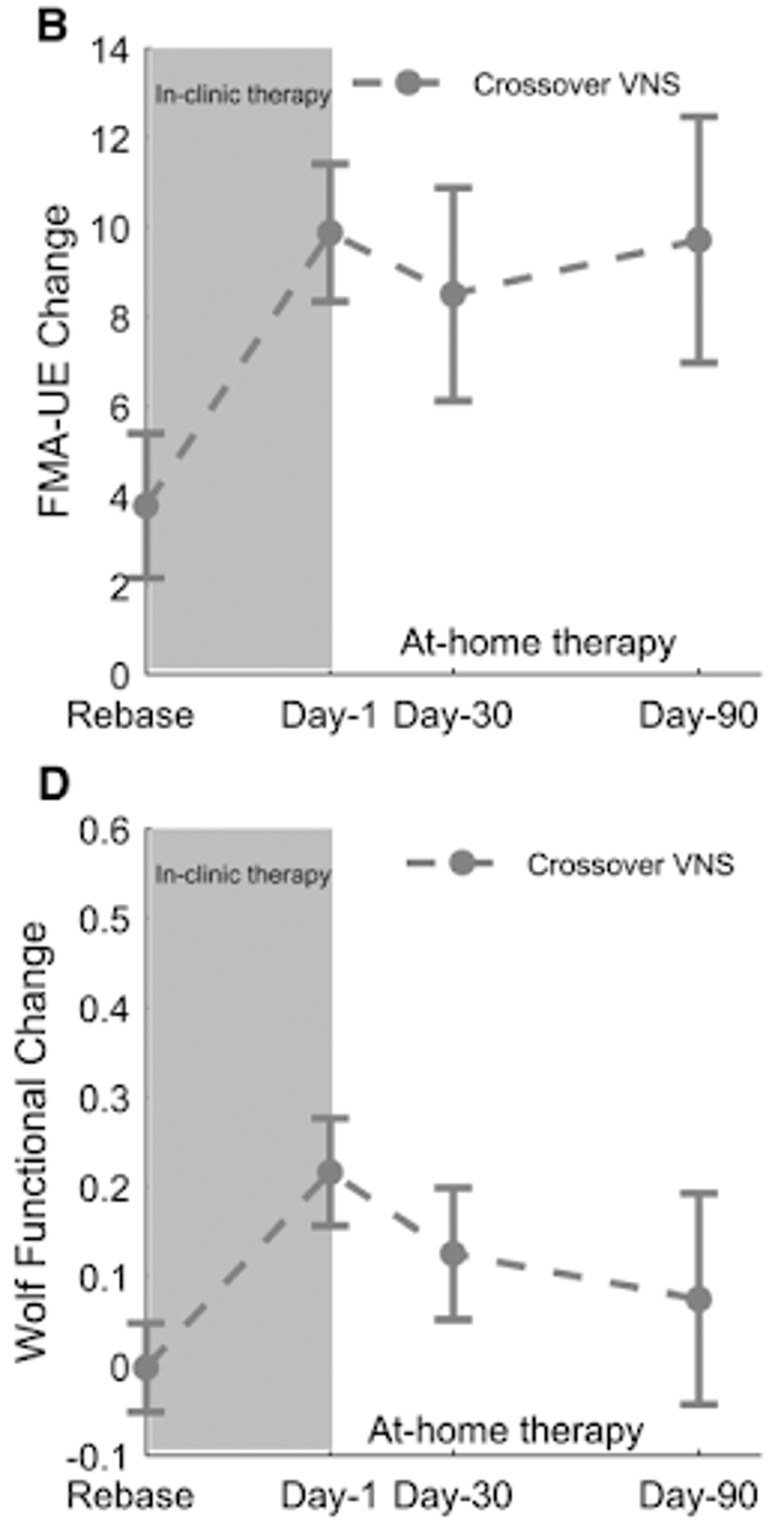

They also treated the control group with the combination treatment following the initial 90-day window. This would test whether further therapy paired with simulation treatment could yield similar results to those who received the combination in the first place.

In the Fugl-Meyer Assessment, resultant scores were similar to the crossover group as the original test group. However, in the Wolf Motor Function Test, results were significantly diminished, suggesting that vagus nerve stimulation is better for patients when paired with initial physical therapy following stroke.

FIGURE 2: Changes in upper arm mobility over time in patients who received vagus nerve stimulation and therapy following an initial round of therapy without stimulation.

These results were replicated and expanded upon in the International Stroke Conference presentation. Not only did this later presentation include over 100 participants who experienced similar improvements in the same scoring methods, but these improvements were sustained even one year following the combination of stimulation and physical therapy, suggesting the treatment could serve as an effective long-term treatment option for post-stoke individuals experiencing limited upper arm mobility.

There are some drawbacks, however, to note when discussing vagus nerve stimulation therapy. Firstly, there are some side effects to consistent electronic stimulation, including neck pain, headache, and nausea. These are typically mild but may be common during use.

Secondly, the device delivering stimulation must be surgically attached, which, in addition to continued use of the device itself, may yield significant costs, especially for those uninsured or underinsured.

Thirdly, and perhaps most significantly, efficacy varies from person to person. While upper arm mobility improved drastically on average, some succeeded more than others. This must be kept in mind when deciding to pursue treatment.

Though ultimately, vagus nerve stimulation therapy stands as a promising avenue in the realm of neuromodulation, offering potential benefits for individuals dealing with various health conditions, from epilepsy to depression. This treatment is part of a new emphasis on bioelectronic medicine. We are helping the body recover from disease by electrical stimulation of the nervous system.

In a post-stroke context, combination therapy is a clear improvement on the reliance on physical therapy alone. As research and technology progress, refining our understanding of the therapy’s mechanisms and optimizing its application, we move closer to unlocking its full potential.