Cancer Therapy And The Intestinal Microbiome

(Posted on Tuesday, July 23, 2024)

A study published in Nature suggests a variation in responses to a cancer immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors may be due—at least in part—to a patient’s intestinal microbiome.

Turning to the Intestines

There are other similar reports that paint a connection between the microbiome—the collection of microorganisms living in a patient’s intestines—and responses to cancer therapies. Mouse studies illustrate how these bacteria can promote antitumor responses to checkpoint inhibitors. A recent paper on vitamin D also underscores this link: mice with increased vitamin D intake respond more readily to anti-PD-1 therapy, but this effect is dependent on the presence of intestinal microbiota. The limitation of these studies is that they may not be reproducible in humans.

A few early trials show that a fecal microbiota transplant could benefit melanoma patients whose cancer has returned after anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors. The transplant from a donor who responds to the therapy can change the intestinal microbiome favorably to overcome inhibitor resistance. However, the responses to the transplant are not guaranteed.

Many unknowns remain, such as the underlying mechanism at play or which strains of bacteria promote this response. A deeper understanding of this mechanism is necessary to develop meaningful therapeutics for people facing relapse or non-response to checkpoint inhibitors—especially as intestinal microbes can vary from person to person for various reasons, including diet, medicines, genetics and more. The study discussed in this article provides some insight into this complex field.

About Checkpoint Inhibitors

Checkpoint inhibitors are a type of cancer immunotherapy approved to treat over 25 different types of advanced cancers, including melanoma, lymphoma and lung cancer. They rely on intravenous infusions of antibodies to interfere with proteins called immune checkpoints. Specifically, the inhibitors target one of three checkpoint proteins: CTLA-4, or partner proteins PD-1 and PD-L1.

Checkpoint proteins act as brakes for the immune system. They are naturally found on the surface of several types of immune cells. They dampen immune cell activity by interacting with partner proteins—for example, a PD-1 checkpoint binding to PD-L1. This safety mechanism turns harmful when co-opted by tumor cells. Tumors can express these proteins and quiet immune cells that would otherwise eliminate them.

Checkpoint inhibitors prevent cancer cells from growing unchecked. The inhibitor antibodies block checkpoint proteins from accessing their binding partners. This blocking interaction allows previously restrained immune cells to recognize and attack tumor cells.

Although some cancers respond to checkpoint inhibitors, others do not. For example, PD-1 inhibitors can elicit a potent 80% overall response rate in Hodgkin lymphoma patients, but a mere 6-22% for ovarian cancer patients. Moreover, many people eventually experience relapse or do not respond to the treatment at all.

Numerous ongoing efforts may address this issue, including identifying biomarkers to predict which patients are more likely to respond to the treatment or combining the therapy with other cancer treatments such as chemotherapy. Alternatively, the answers we seek may reside in our intestines.

Bacteria and the PD-L2-RMGb Pathway

In their study, Harvard researcher Dr. Arlene Sharpe and colleagues embarked on a series of experiments using mouse tumor models. They identified specific strains of bacteria that encourage antitumor responses to checkpoint inhibitors and a potential underlying mechanism. The work highlights two molecules in particular: PD-L2 and RMGb.

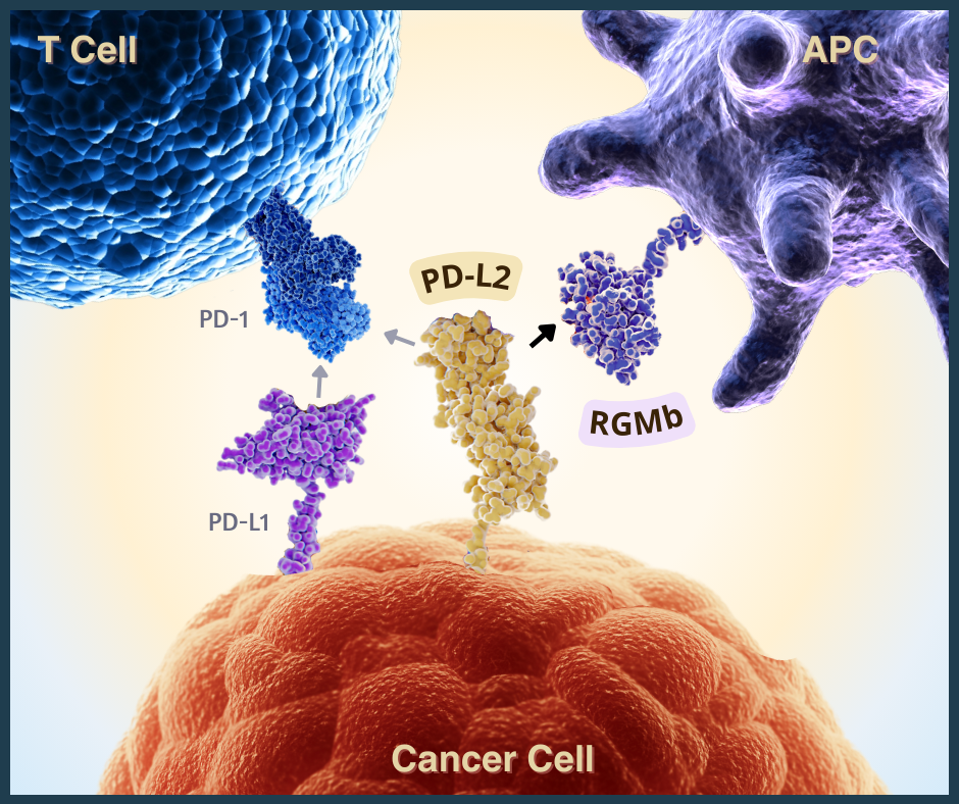

Programmed death ligand 2, or PD-L2, is a checkpoint protein found on the surface of specific immune and cancer cells. As illustrated in Figure 1, this molecule is known to bind to PD-1 checkpoint proteins on T cells and discourage T cell responses, similar to PD-L1 molecules. However, unlike other checkpoint targets, a PD-L2 targeting inhibitor has not yet been approved by the FDA.

The responses of mice with different intestinal microbes pointed to PD-L2 as a critical factor in mediating antitumor responses to cancer immunotherapy. Mice were seeded with microbiota from patients that either responded well to checkpoint inhibitors or gained little benefit. The differences in bacteria influenced their responses to immunotherapy.

Mice who received microbiota from responder patients presented lower levels of PD-L2 on antigen-presenting cells, key immune system defenders. These cells scan for foreign or abnormal proteins and present these pieces of these proteins to T cells for destruction. In contrast, mice treated with bacteria from patients who didn’t respond to the treatment displayed high levels of PD-L2. A particular strain of bacteria called C. cateniformis was found to downregulate PD-L2 expression on certain immune cells and, in turn, enhance antitumor responses to cancer immunotherapy.

If a high expression of PD-L2 prevented antitumor responses, similarly to PD-L1 checkpoints, did it undergo a similar pattern—binding to PD-1 and inhibiting T cell function? Further testing revealed that this was not the case. The mice did not improve with anti-PD-1 therapy as expected. Rather, results improved when blocking a novel PD-L2 binding partner called Repulsive Guidance Molecule b.

Repulsive Guidance Molecule b, or RGMb, functions differently to PD-1 checkpoints. These molecules reside in various tissues such as the lungs, where they help prevent excessive inflammation. The experiments demonstrate that blocking interactions between this molecule and PD-L2 promoted microbiome-dependent antitumor responses to PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in mouse models. The findings emphasize specific intestinal bacteria and immune molecules’ role in mediating antitumor responses to checkpoint inhibitors.

Figure 1: PD-L2 interactions with two checkpoint proteins: PD-1 and RGMb. Blocking the PD-L2-RGMb pathway may lead to increased antitumor responses during anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor therapy. [Abbreviations: APC, antigen-presenting cell; PD-1, programmed cell death protein; PD-L1 and PD-L2, programmed death ligands 1 and 2; RGMb, repulsive guidance molecule b]

ACCESS HEALTH INTERNATIONAL

Takeaways

Checkpoint inhibitor therapy works against some, but not all, tumors. Treatment options are needed for patients who have never or no longer respond to the therapy. According to this study, building towards a combination treatment may be possible. Co-administering inhibitors that target PD-L2 molecules and the PD-1/PD-L1 may be needed to overcome treatment resistance. This microbiome-dependent interaction can influence antitumor responses in mice, but further research is necessary to solidify this potential connection in humans.