NBA Study Reveals The UK Variant May Last Longer In Human Hosts

(Posted on Friday, February 19, 2021)

Random variation is an essential component of all living things. It drives diversity, and it is why there are so many different species. Viruses are no exception. Most viruses are experts at changing genomes to adapt to their environment. We now have evidence that the virus that causes Covid, SARS-CoV-2, not only changes, but changes in ways that are significant. This is the seventeenth part of a series of articles on how the virus changes and what that means for humanity. Read the rest: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, part seven, part eight, part nine, part ten, part eleven, part twelve, part thirteen, part fourteen, part fifteen, and part sixteen.

ATLANTA, GA – FEBRUARY 03: Luka Doncic #77 of the Dallas Mavericks drives to the basket during the first half against the Atlanta Hawks at State Farm Arena on February 3, 2021 in Atlanta, Georgia. NOTE TO USER: User expressly acknowledges and agrees

GETTY IMAGES

As variants account for a more significant proportion of global Covid-19 day-by-day, we have to adjust our public health policy accordingly. SARS-CoV-2 variants possess a well-documented bag of tricks. Some are immune-evading, like the South African and Brazilian variants, and others are far more transmissible, like the United Kingdom variant (B.1.1.7). A recent study from the Harvard University School of Public Health suggests that B.1.1.7 may even remain in human hosts nearly twice as long as non-B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2, extending the potential contagious period from about eight days to thirteen days.

The study was conducted in conjunction with the National Basketball Association (NBA). In Summer 2020, the NBA restarted their season after it was paused by the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. The players involved were isolated at Disneyworld resort and were administered daily Covid-19 testing. That practice expanded to the recently begun 2020-2021 season, and Harvard University took the opportunity to genome sequence the basketball players’ samples for research purposes.

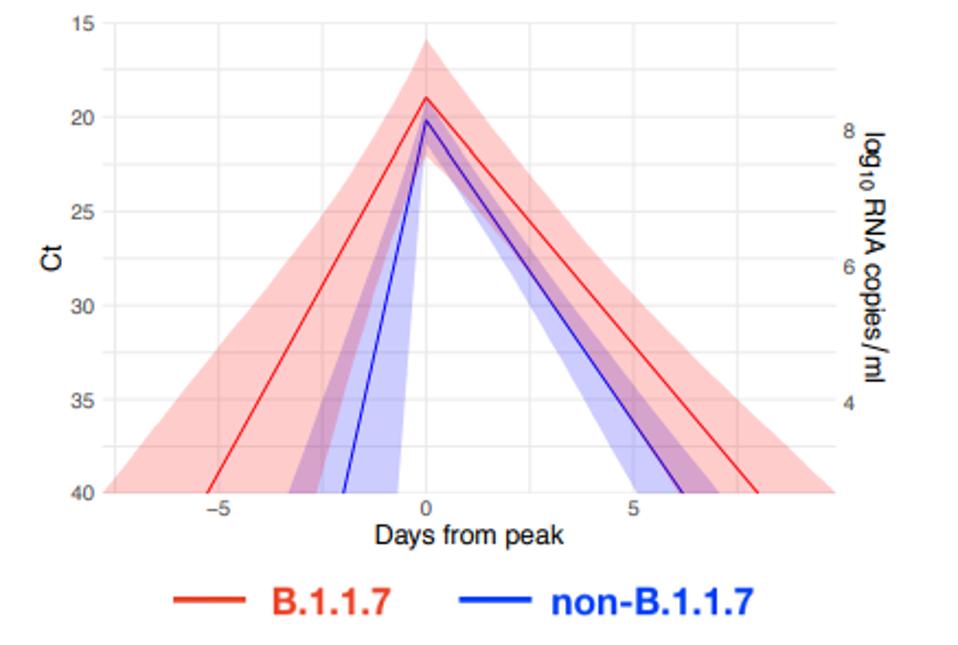

The Harvard researchers identified seven samples infected with B.1.1.7 among a cohort of 65 individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. “For individuals infected with B.1.1.7, the mean duration of the proliferation phase was 5.3 days, the mean duration of the clearance phase was 8.0 days, and the mean overall duration of infection was 13.3 days. These compare to a mean proliferation phase of 2.0 days, a mean clearance phase of 6.2 days, and a mean duration of infection of 8.2 days for non-B.1.1.7 virus.”

Additionally, peak viral concentrations for B.1.1.7 were slightly higher than non-B.1.1.7 patients, 8.5 log10 RNA copies/ml for B.1.1.7 and 8.2 log10 RNA copies/ml for others on average. In other words, the B.1.1.7 patients experienced extended infections with more viral particles, as displayed by the graph above. The overall viral burden for those with B.1.1.7 was higher than their non-B.1.1.7 counterparts on average for a greater period of time.

The extended duration of B.1.1.7 is likely associated with its increased transmissibility. The Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention (CDC) state that B.1.1.7 transmits at 50% the rate that non-B.1.1.7 SARS-CoV-2 is capable. The virus is adjusting to our immune responses, and now, we see the B.1.1.7 capable of withstanding the human immune response over 60% longer than previous viruses. Respiratory viruses typically have shorter lifespans and must jump from host to host quickly to survive and spread, but this virus sticks around for a while. Longer infections mean the virus has the opportunity to spread to more people, increasing infections, which leads to greater spread, and the positive feedback loop continues.

This is deeply concerning. As I’ve written about for Forbes, the CDC recommends that infected people remain in quarantine for 14 days but only require seven or ten days of quarantine based on the patient’s individual circumstances. If the B.1.1.7 variant infects someone and they only quarantine for seven to ten days, they may go on to infect others thinking they are free of the virus.

In response to the growing concerns of rapidly spreading SARS-CoV-2 variants, the Chinese government increased their required isolation period to three weeks in the past few months. This more than encompasses the 13.3-day duration the Harvard researchers observed from the B.1.1.7 variant.

While the authors of this research focus on transmissibility, it may also go a long way to understand virulence. Those that are infected with B.1.1.7 have a higher probability of dying from the infection. Spike protein mutations like those found in B.1.1.7 increase transmissibility by increasing affinity to the human ACE2 receptor. That may not be the whole story. During the extended period of time B.1.1.7 survives within the host, it must fend off the immune system. SARS-CoV-2 specifies immune modulators like ORF3a, ORF8, and others. These may be altered during the virus’s extended stay, resulting in greater virulence and chance of death.

If we are to control these variants before they become out of hand, we need to adjust public health policy accordingly. As the Chinese have done, we should extend quarantine requirements to three weeks. Of course, people cannot be out of work for three weeks without pay. As I have been championing for months upon months, the federal government must assist those in isolation, financially, as well as with medical supplies and shelter if necessary. We must also further understand how B.1.1.7 and other variants pull off these dangerous tricks of immune-evasion, increased transmissibility, and virulence promotion.

This data adds to the growing narrative around B.1.1.7 and SARS-CoV-2 variants in general. They are dangerous and adaptive, growing more accustomed to the human immune response with every infection. We must similarly adapt our public health approach to fight back and control these viral variants before we see a resurgence of the virus in the near future.

Originally published on February 19, 2021.